N.B. #1: A couple years ago, I wrote a nerdy article for Yahoo about the history of and technical challenges surrounding frame rates. Unfortunately, Yahoo removed its Featured Contributor website, so the articles I wrote for them no longer exist. This is a fragmented attempt to reconstruct and expand on my original piece.

David S. Cohen, writing for Variety last December on director Peter Jackson's approach to the aesthetics of the second installment of The Hobbit Trilogy:

"It was interesting to try to interpret what people’s reaction was,” Jackson says. He concluded the problem was that the image looked like HD video, and was simply sharper than people are used to in cinema.

“So what I did is work that in reverse,” says Jackson. “When I did the color timing this year, the color grading, I spent a lot of time experimenting with ways we could soften the image and make it look a bit more filmic. Not more like 35 mm film necessarily, but just to take the HD quality away from it, which I think I did reasonably successfully.”

Jackson’s tweaks sound like a post-mortem stopgap, as if he’s trying to amend a poorly executed paint job. The first film has a simple, but fatal, flaw: it doesn't have a point-of-view. The filmmakers lose track of whose story to tell — it should be Bilbo Baggins’s, obviously — and every aspect of the production, from the acting to the cinematography to the production design to the sound design, suffers from this lack of focus.

But this matter can’t be closed with that terse a verdict. By shooting The Hobbit at 48 frames per second (FPS), Jackson and his collaborators made a worthy attempt at weaning audiences off movies that remain needlessly beholden to a recording / filming / projection standard of 24 FPS.

An excerpt, from research I did for that now-lost article from 2012:

For over 80 years, films have been shot and projected at 24 FPS. Studios didn’t establish this standard because it was perfect; they just needed film to run at a regular speed for playing back sound…

The cinema “look” we are familiar with was just a compromise from the late 1920s, after a sound engineer averaged out how fast theaters were projecting films. Many theaters at the time played their movies back faster than was intended, to get audiences in and out of their seats faster.

If you've made it this far, you owe it to yourself to watch this fantastic presentation on the current state of frame rates by Bruce Jacobs, Mark Schubin, Douglas Trumbull, and Larry Thorpe, who are, collectively, formidably erudite.

Off the bat, Mark Schubin offers this money quote:

There is absolutely nothing special about 24 frames per second. There is no particular psychological reason for it, no mathematical reason for it.

The Man has been giving my classmates and me a tour of his company’s state-of-the-art facilities these past several hours. Unlike many peons working in Hollywood, he’s dressed sharply, in a fine suit and dress shoes. The company recently completed an impressive restoration of a 50-year-old epic, so I believe the Man’s sartorial instincts are justified.

But he’s been unintentionally rubbing my cinematography professor and classmates the wrong way with certain off-the-cuff remarks. For instance, his company’s post-production capabilities allow producers to “fix the frame" if they see something they don’t like. Things come to a head when the Man flippantly says that he and his company have never come across a project shot in 30 FPS.

My professor speaks up: “I’m a fan of 30 frames per second. It’s a shame it never really caught on.”

The Man remains silent for several, pregnant seconds. He sticks a hand in his jacket pocket.

“Really.”

“Yes.” My professor sticks to his guns. “I always felt 24 frames per second had too much strobing. It just has too many compromises.”

There's a truth to what my professor says. And there's a reason why Douglas Trumbull spent the 1970s and '80s developing Showscan. The ASC Manual devotes scores of pages to charts that illustrate how fast a camera operator should pan if they're using different focal lengths, because it's easy for objects to look like they're strobing, particularly on larger screens. Another excerpt from my research:

There tends to be a lot of flickering at 24 FPS, which becomes particularly noticeable the larger and brighter a screen becomes. If a character moves a bit during an IMAX screening, for instance, she’ll move the equivalent of several feet on-screen. That displacement can be jarring and exhausting for audiences to endure.

Consider It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. The filmmakers, knowing that their film would be projected on larger screens, chose to shoot at 30 FPS. They understood that audiences would inexplicably feel more exhausted if they had to endure a three-hour movie projected at 24 FPS, because they would unconsciously attempt to fill in the on-screen displacement, those gaps between frames and movements.

Solutions / Paradigms / the Future

In The Hobbit, was anyone else bothered by the way characters moved when they were in smaller spaces, like the hobbits’ homes in the Shire? Something about the higher frame rate made them look awfully twitchy, like trapped hummingbirds flitting about in a flask.

In order for movies with higher frame rates to catch on, filmmakers and actors need to develop a new aesthetic, a new approach to their craft.

Here are a few changes that would help audiences to be more accepting of movies shot with higher frame rates, under the current paradigm:

- Production designers and art directors may have to build larger-than-normal sets.

- Camera operators and dolly grips may have to slow down their movements, so audiences don’t perceive their work as being subjected to a VHS-style fast-forward.

- Actors may have to modulate their timing and blocking, to avoid the trapped hummingbird effect.

Higher frame rates have the potential to create new paradigms that enable filmmakers to expand audience’s expectations for what’s possible with recorded media. But this potent tool must be thoroughly considered from the very start of a project (i.e., while writing a script)—not two movies into a multi-billion-dollar trilogy.

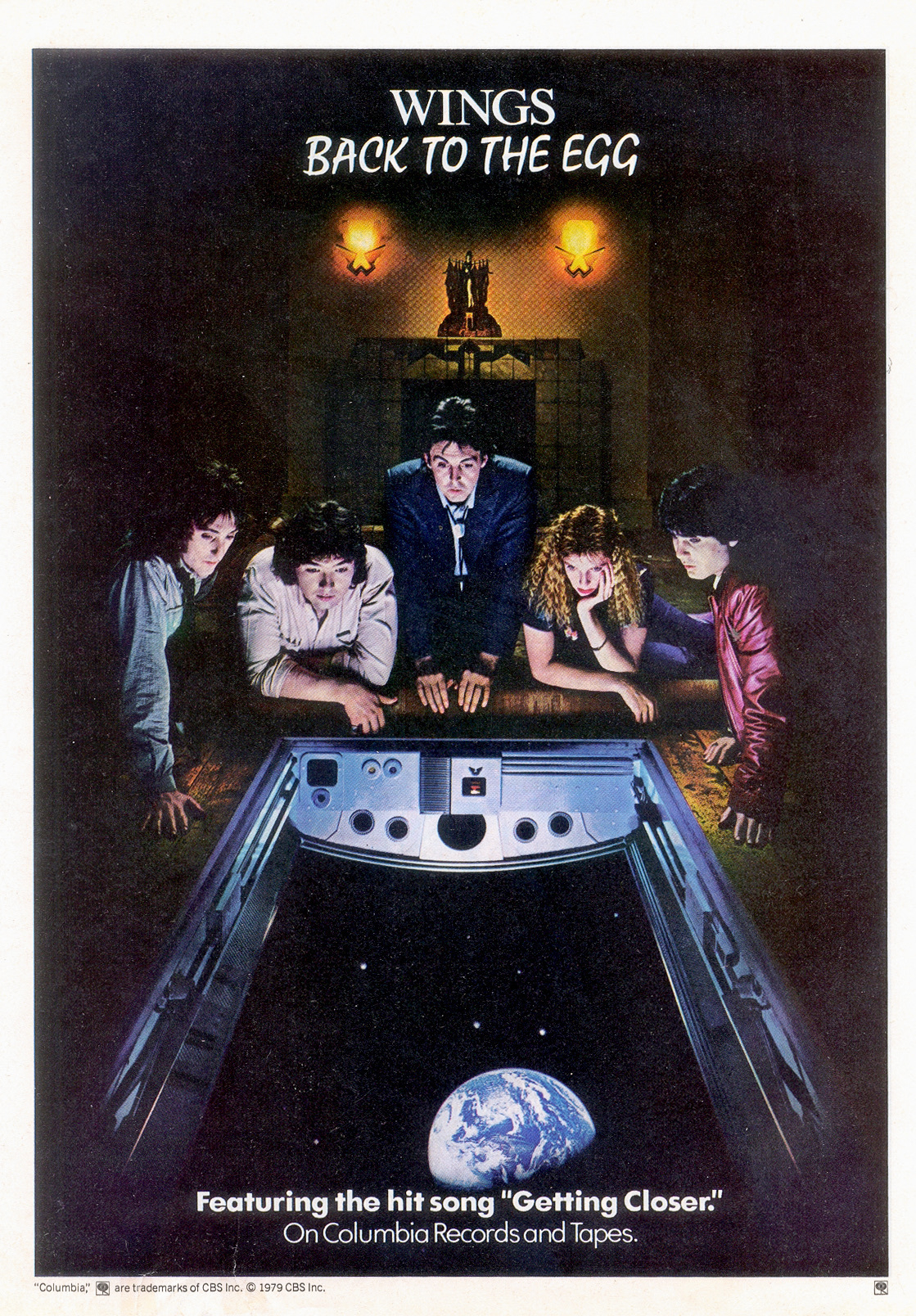

N.B. #2: This post’s title was inspired not by Back to the Future, but by the 1979 Wings album, Back to the Egg.[1] My former housemate Judah hung an LP of Back to the Egg on the wall of his bedroom because it made for a decent poster. So even though I’ve never listened to the album, I nonetheless have fond memories associated with visiting Judah’s room and seeing that bizarre photo.

-

Its release was ultimately overshadowed by Japanese officials arresting and detaining Paul McCartney for possessing a shitload of pot. ↩